By Timothy Langley, Representative Director, Langley Esquire

May 2025 – TokyoWhen the price of rice rises in Japan, ripple effects are swift and unforgiving—economic, political, and cultural. The fragility of Japan’s food system was thrust into the spotlight last week when Agriculture Minister Taku Etō was forced to resign after joking to supporters that he had “so much rice, it’s under my bed.”

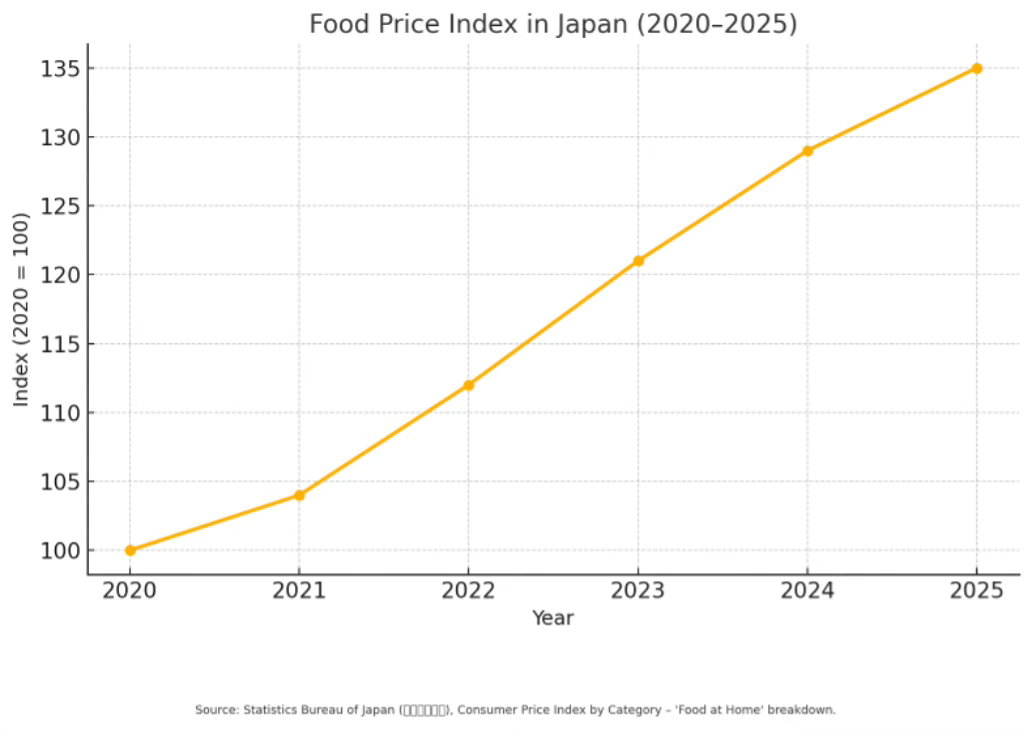

What might once have been dismissed as rustic banter triggered a political storm. Prices have doubled in a year, hoarding is rampant, and supply chain anxieties are mounting. With Prime Minister Ishiba already walking a tightrope ahead of two major elections, the faux pas proved politically fatal.

Enter Shinjirō Koizumi.

Telegenic and tactically reserved, Koizumi has now assumed the Ministry of Agriculture portfolio—an appointment that doubles as battlefield promotion and succession signal. Japan’s food system, long taken for granted, is entering an era of hard reckoning. And Koizumi is now its face. He promises to slash by half the price-of-rice within 30 days!

Behind the Abundance: Japan’s Food Balancing Act

To live in Japan is to experience a daily illusion of culinary abundance. Convenience store sandwiches are fresh to the minute. Supermarkets brim with glossy produce and imported cheeses. Sushi bars serve fish so fresh it seems to swim onto your plate.

But this abundance belies a dangerous dependency.

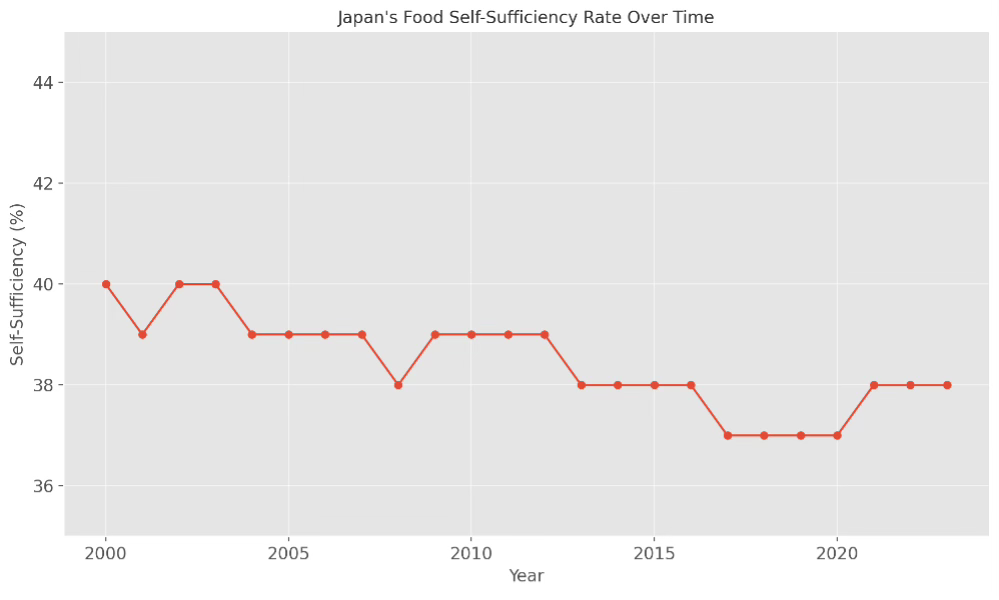

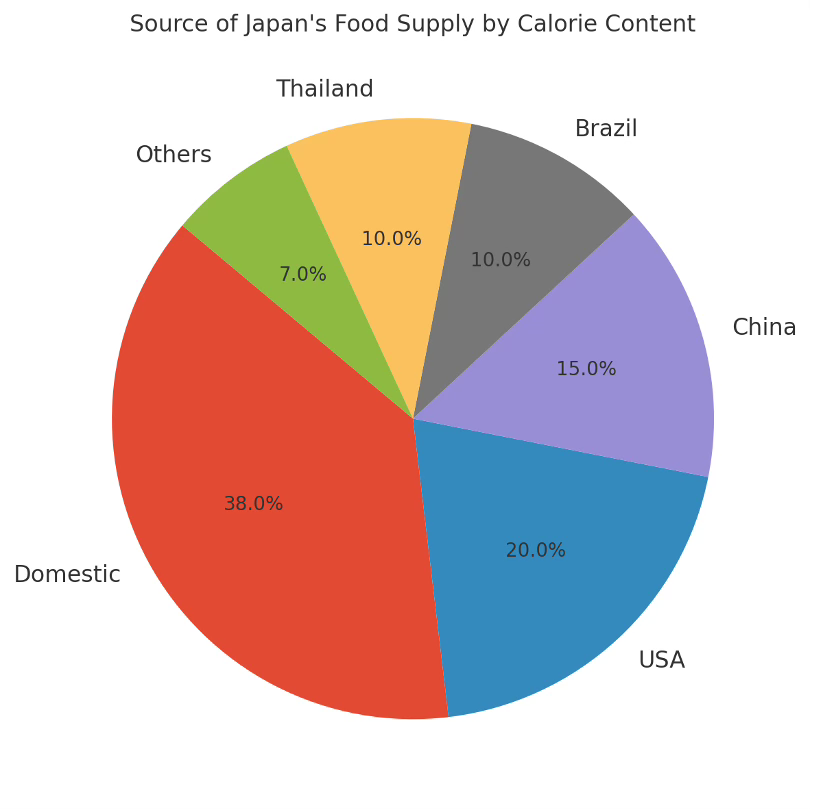

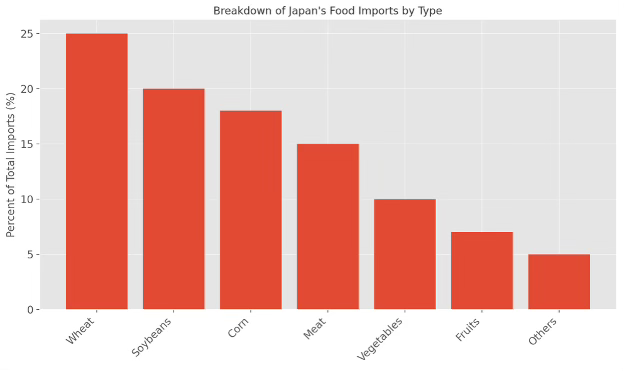

Japan’s calorie-based food self-sufficiency (~38%) is at a level considered dangerously low for any developed country. The rest is imported, including:

· Wheat from the U.S. and Canada

· Soybeans and corn from Brazil and Argentina

· Beef from Australia and the U.S.

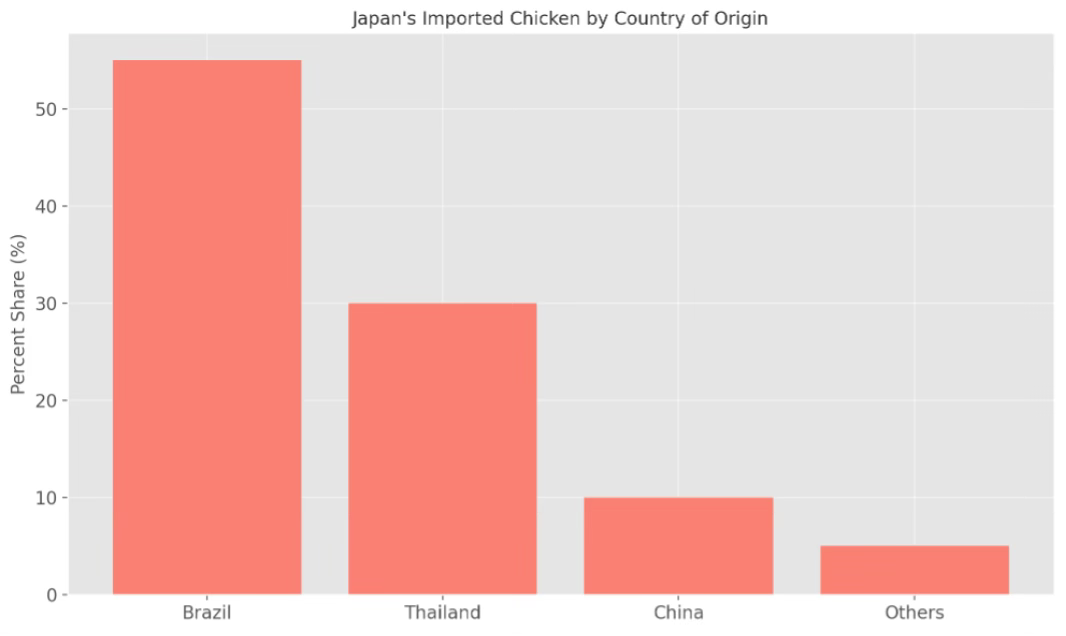

· Chicken—frozen, in volume—from Thailand, China, and Brazil

· Vegetables such as garlic and onions from China

Japan’s Food Self-Sufficiency Rate by Calorie (%)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), Japan – 'Food Self-Sufficiency Ratio' (most recent annual white paper).

The lifeblood of this system is the vast logistical ecosystem managed by trading giants like Marubeni, Mitsui, and Itochu. These firms act as silent guarantors, ensuring that global weather shocks, shipping slowdowns, or geopolitical rifts don’t disrupt Japan’s food supply. But lately, their job is getting harder.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF)

Rice: Sacred Commodity, Strategic Weak Point

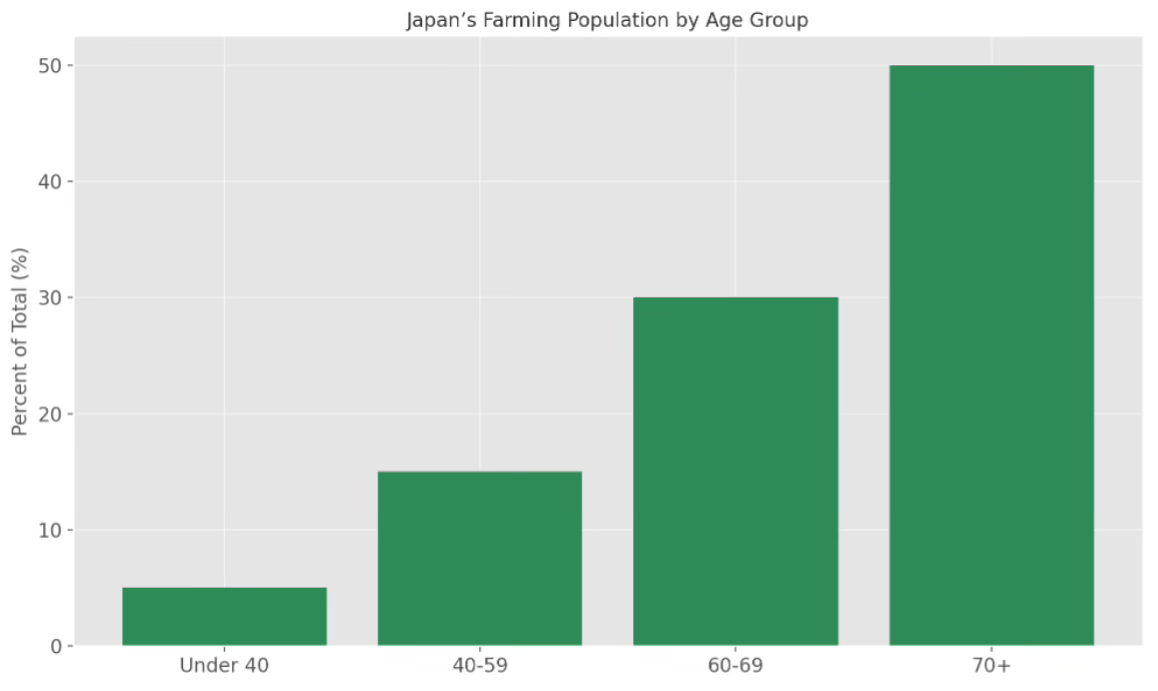

Rice is the cultural cornerstone of Japan’s diet—and for decades, its most protected crop. It is price-controlled, politically sensitive, and grown by a vanishing population of small-scale farmers, most of whom are now in their 70s.

Japan still grows nearly all of its rice domestically. But this is no longer a guarantee. Climate change, aging labor, and the rising cost of fertilizer have pushed thousands of farmers out of the business. Rural depopulation has left paddies abandoned. Mechanization helps, but not enough. Costco is selling California rice as other non-standard channels are springing open, too.

Source: MAFF, Survey on Agricultural Workforce and Age Distribution.

In response to price pressures and whispers of shortfalls, wholesalers and distributors began hoarding. By early 2025, retail prices had doubled. The government issued quiet reassurances, but Etō’s gaffe shattered the illusion of control. His dismissal was swift.

Koizumi’s Moment: Food as National Security

Koizumi’s appointment is no accident. The son of a former Prime Minister, he’s long been a contender. By giving him MAFF, Prime Minister Ishiba hands him both a crucible and a stage.

And rightly so. Food is now a national security issue.

Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), White Paper on Food Self-Sufficiency.

· Ukraine war disrupted wheat imports;

· China’s fertilizer, fish, vegetable & fruit bans roil markets;

· Climate shifts have upended seasonal growing cycles from California to Hokkaido.

Japan is increasingly vulnerable not because it lacks food—but because it lacks control. The political question now is: can Koizumi restore trust while reforming The System?

Policy at a Crossroads: What Must Be Done

Koizumi’s immediate imperatives include:

· Revitalizing rural farming with smart-agriculture incentives and training

· Revising subsidies to attract younger entrants and support cooperative models

· Bolstering domestic grain reserves as a true emergency buffer

· Reframing dietary patterns to reduce overreliance on imported staples

But these are uphill battles. Cultural inertia, market resistance, and vested interests in the agricultural lobby will not yield easily.

What’s at Stake?

· Aging Farmers: The average rice farmer is now in their 70s. There are no successors.

· Urban Amnesia: Most city dwellers are detached from food sources—and the system’s fragility.

· Global Interdependence: Japan’s food prices are exposed to droughts in California, fertilizer pricing in Belarus, and labor disruptions in Brazil.

· Geopolitical Leverage: Control of food imports is a tool of soft power—and coercion.

Despite it all, grocery shelves remain stocked. Bento boxes appear as if by magic. But the system is operating on thinner ice than most realize.

Illusion or Imperative?

Japan’s food system is both a marvel and a mirage. And her food-culture is world renowned! It has delivered safety, abundance, and predictability. But increasingly, this rests on precarious foundations including the whims of foreign markets, an aging domestic labor pool, and a policy framework rooted in past global abundance.

Koizumi will offer fresh thinking for sure, but he will need political capital, policy courage—and cultural imagination. Steering such a ship will be difficult, so whether Japan can shift from reacting into planning, from global patchwork into home-grown resilience, will define its food future.

The question is not “can Japan feed itself?” (because it cannot); the REAL question is, “does Japan dare to prepare for, i.e., telegraph, an approaching collapse?”

Japan’s Astonishing Food Balancing Act

Japan is only about 38% self-sufficient in calories—a figure that has declined steadily from nearly 79% in 1960. Wheat, corn, soybeans, and cooking oils are almost entirely imported. Chicken arrives frozen from Brazil, Thailand, and China. Beef? Primarily Australian or American. Even basic vegetables like onions, garlic, and potatoes often have international origins. This dependency creates a remarkable paradox: gleaming supermarket shelves masking a logistical and geopolitical tightrope.

Japan’s massive trading houses—Mitsui, Marubeni, Sumitomo, and Itochu—perform a daily logistical ballet, while the Ministry of Agriculture closely monitors global crop reports and shipping lanes as if they were interest rates.

The Rise of Koizumi and Policy Implications

Koizumi’s appointment as Agriculture Minister is more than political theater. It positions him at the intersection of Japan’s most urgent vulnerabilities: aging farmers, climate-driven yield risks, and global supply volatility. Koizumi is expected to champion incentives for new farmers, regional revitalization via smart-agriculture technologies, and dietary diversification. However, implementing these policies will face institutional drag—MAFF’s bureaucracy, aging co-ops, and land title fragmentation will resist abrupt change.

Consider this: not so very different from the enormous “akiya” (abandoned homes) problem, over 1.5 million hectares of farmland in Japan lie unused, yet consolidating these into viable farms is mired in legal and administrative red tape.

Global Reference Point

South Korea faces a similar dependency but has proactively built strategic grain reserves. Taiwan, meanwhile, has focused on resilience through urban agriculture and trade diversification. Japan, despite its advanced logistics, lacks a comprehensive emergency food plan beyond rice stockpiles.

A national strategy on food security must now include contingencies for export bans, climate shocks, and geopolitical instability.

Conclusion: Illusion or Imperative?

Japan’s food system is a wonder of efficiency—but dangerously brittle. Koizumi may bring visibility and energy, but policy courage will be required to drive generational change.

Without stronger succession pipelines for farmers, incentives for crop diversity, and clearer strategic stockpiles, Japan’s food mirage could shatter with the next shock.

The question isn’t just 'Can Japan feed itself?'—because in strict calorie terms, it already cannot. The true question is: can Japan anticipate and act before collapse is forced upon it by a distant drought, trade war, or maritime blockade?

-----(end)-----

I live in Shinanomachi, Nagano and have been writing and speaking for some time about the imminent implosion of Japanese agriculture. Your analysis lays out the challenges ahead better than anything that I have read. Good job and give my regards to Tim, an old friend from my days at the US Embassy, with Microsoft and within the ACCJ.

Thank you, very nice summary of an important problem.